In the fall of 1989 a new discovery in this area proved to be one of the most historic of the early Canadian steamboats, the iron hulled side-wheeler Cornwall.

The following is an article written for The Kingston Whig Standard by One of the people who located the wreck. Diver and marine historian: Rick Neilson.

Launched in Montreal in 1854 as the Kingston, she was one of the finest Canadian steamboats of her day on the Upper St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario. Indeed, when the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) toured Canada in 1860, she was chosen to be his ‘floating palace.’ Stained glass windows, pianos, and luxurious carpeting comprised part of her decor. In 1872 she was gutted by fire while off Grenadier Island in the St. Lawrence River. Rebuilt as the Bavarian, she burned a second time in the fall of 1873. The iron hull, rebuilt yet again, at Power’s shipyard at Kingston, was this time christened the Algerian. Under this name she served in the Royal Mail Line for the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company until the turn of the century, running between Toronto and Montreal. Renamed the Cornwall in 1905 she gradually assumed a stand-by role, filling in when one of her newer, faster line mates had a breakdown.

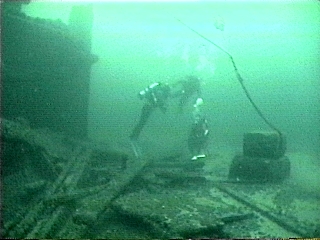

Photo by Rick Rogers.

Near the end of 1911 she was purchased by the Calvin Company of Garden Island, opposite Kingston. In their hands she underwent a remarkable transformation. The Calvin’s weren’t interested in passengers, their business since the 1830’s had been the movement of lumber and ship building, with a towing and wrecking business on the side. They removed much of the upper works and added salvage equipment and a derrick for ‘lightening’ the cargo of stranded vessels. After two highly remunerative seasons the Cornwall was sold to the Donnelly Salvage and Wrecking Company, who used her for many more years as a wrecker. As late as 1928 they still considered her the flagship of their fleet. With her 40 ton derrick, clamshell outfit, 12 inch rotary steam pumps, diving equipment, air compressor lifting jacks, wrecking hawsers, syphons, steam connections and steel hose, she was well equipped to fulfill her role of rescuing vessels in trouble.

Photo by Rick Rogers.

In the winter of 1928, the Donnelly Salvage & Wrecking Co. was one of several Great Lakes salvage outfits purchased and combined to form Sin Mac Lines, later Sincennes-McNaughton Tugs Ltd.

Shortly thereafter her owners decided that the Cornwall had finally outlived her usefulness. Her iron hull was tired after 75 years of continuous use. The late Vic Ruttle of Portsmouth, an old Donnelly hand, described her last voyage. About 1930, just before Christmas, they towed her out in a snow storm. Her engine had been removed but her boilers, paddle-wheels and cabins were intact. Not being anxious to hang around, the crew hurried her on her way by the generous use of dynamite. He wasn’t sure of her exact location but thought she was somewhere near Amherst Island.

When found she was pretty much as Mr. Ruttle described her. Sitting upright on the bottom in 70 feet of water, the 176 foot long iron hull is split open in several places, either from the dynamite or impact with the bottom. The engine is missing from between the large a-frame, but the boilers are still in place, sticking some 20 feet off the bottom. The ten bladed feathering paddle wheels, 20 feet in diameter, are intact. The cabins are all gone but a great deal of wood-work lies on the bottom around the outside of the hull. Scattered throughout the wreckage are other items of interest; wooden barrels, tools, steam pipes, a bed, a ladder. At the bow a large piece of fore deck still has the windlass in place; a small engine and port-holes may also be seen here.

The sandy bottom and relatively shallow depth ensure that there is plenty of light; visibility during the summer is often in the 15-20 foot range. The lack of silt inside the hull allows divers to examine the construction methods used on what is only the fourth commercial iron vessel on the Great Lakes. A mooring was installed in the fall by Preserve Our Wrecks, Kingston to help protect this important piece of marine heritage.

The wooden hull of the Comet, built in 1848, and the iron hull of the Cornwall, built in 1854, rest on the bottom within two miles of each other. Where else in the Great Lakes can divers explore two side wheelers in one day?

Photo by Rick Rogers.

Around the year of Canada’s 100th birthday a 40 ft wooden trawler hull was started in Shelborne Nova Scotia.. The craft was being built for Ken and Lois Jenkins of Port Credit Ontario. The hull was brought to Port Credit and completed in their back yard. In 1968 it was launched.. The completed boat was christened The Effie Mae.. Around 1980 the Effie became the first live aboard dive charter boat in the Kingston area. In 1987 Ken sold the Effie to Ted and Donna Walker. Ken succumbed to cancer and died the following year. Ted and Donna started in 1987 to run charters out of Kingston and continued to the end of the 1992 season.. Ted was transferred out west. So the Walker family decided to sell their beloved Effie.. Finding no suitable buyers and not wanting their beloved Effie broken up or just left to rot. They decided to donate the hull for sinking to Preserve Our Wrecks Kingston. In the spring of 1993 they ran her for the last time to the Metal Craft Dry dock to be made ready for sinking.

Around the year of Canada’s 100th birthday a 40 ft wooden trawler hull was started in Shelborne Nova Scotia.. The craft was being built for Ken and Lois Jenkins of Port Credit Ontario. The hull was brought to Port Credit and completed in their back yard. In 1968 it was launched.. The completed boat was christened The Effie Mae.. Around 1980 the Effie became the first live aboard dive charter boat in the Kingston area. In 1987 Ken sold the Effie to Ted and Donna Walker. Ken succumbed to cancer and died the following year. Ted and Donna started in 1987 to run charters out of Kingston and continued to the end of the 1992 season.. Ted was transferred out west. So the Walker family decided to sell their beloved Effie.. Finding no suitable buyers and not wanting their beloved Effie broken up or just left to rot. They decided to donate the hull for sinking to Preserve Our Wrecks Kingston. In the spring of 1993 they ran her for the last time to the Metal Craft Dry dock to be made ready for sinking.

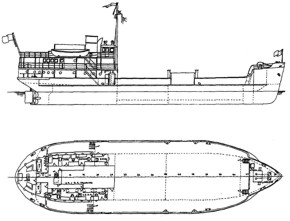

A Collingwood Ship yard built The Ottawa Maybrook and a sister ship during the last days of World War II, they were originally designed as 206 ton, 164ft, class C Coastal Freighters.

A Collingwood Ship yard built The Ottawa Maybrook and a sister ship during the last days of World War II, they were originally designed as 206 ton, 164ft, class C Coastal Freighters. That is until a group of concerned Marine enthusiasts and divers formed a company and took the ship over with the express purpose of sinking her as a dive site in an area protected from the prevailing south west wind. The idea was to provide a safe and interesting dive site accessible in all kinds of weather. At the same time saving the ship from the wreckers torches.

That is until a group of concerned Marine enthusiasts and divers formed a company and took the ship over with the express purpose of sinking her as a dive site in an area protected from the prevailing south west wind. The idea was to provide a safe and interesting dive site accessible in all kinds of weather. At the same time saving the ship from the wreckers torches.

The Munson was a Belleville based steam powered dredge. In the year 1890 it was being towed back to Belleville after completing a job in Kingston by the Emma Munson. About a mile southeast of Collins Bay the vessel started to take on water and sank just off Lemoines Point. It sits upright in 112 feet of water. It’s large shovel lays to the north, the electric generator that is home to a ling cod, is still mounted on the upper deck. A steam boiler, steam engine, plus the many other artifacts still present make this wreck a worthwhile dive. It is intact with the exception of the cabin siding which has fallen off. The wreck is marked with a mooring bouy supplied by

The Munson was a Belleville based steam powered dredge. In the year 1890 it was being towed back to Belleville after completing a job in Kingston by the Emma Munson. About a mile southeast of Collins Bay the vessel started to take on water and sank just off Lemoines Point. It sits upright in 112 feet of water. It’s large shovel lays to the north, the electric generator that is home to a ling cod, is still mounted on the upper deck. A steam boiler, steam engine, plus the many other artifacts still present make this wreck a worthwhile dive. It is intact with the exception of the cabin siding which has fallen off. The wreck is marked with a mooring bouy supplied by

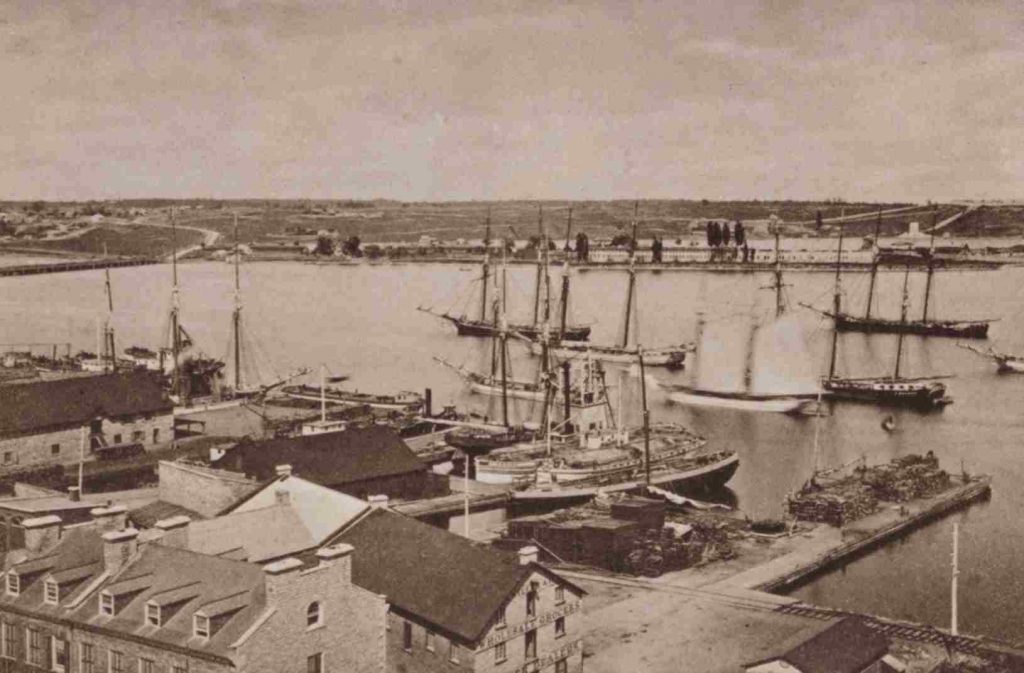

For the thirteen souls on board and making the trip to Kingston this day, things couldn’t have looked brighter. The day was sunny with a nice fresh breeze out of the south west. The ships three large masts could carry plenty of sail, so the trip was going to be fast and enjoyable. Captain Smith was not aboard that day, his sixty five year old mate William Watkins was a seasoned sailor. The second wife of the captain and five of their seven children were on board. As well Mr. Neil MacLellan, a deck hand, had received permission to bring his wife, their eighteen month old baby, and a nephew along. The captain’s brother, William Smith, was also on board. Rounding out the crew was a deck hand by the name of George Cousins. In all 13 people were on board that fateful day.

For the thirteen souls on board and making the trip to Kingston this day, things couldn’t have looked brighter. The day was sunny with a nice fresh breeze out of the south west. The ships three large masts could carry plenty of sail, so the trip was going to be fast and enjoyable. Captain Smith was not aboard that day, his sixty five year old mate William Watkins was a seasoned sailor. The second wife of the captain and five of their seven children were on board. As well Mr. Neil MacLellan, a deck hand, had received permission to bring his wife, their eighteen month old baby, and a nephew along. The captain’s brother, William Smith, was also on board. Rounding out the crew was a deck hand by the name of George Cousins. In all 13 people were on board that fateful day.